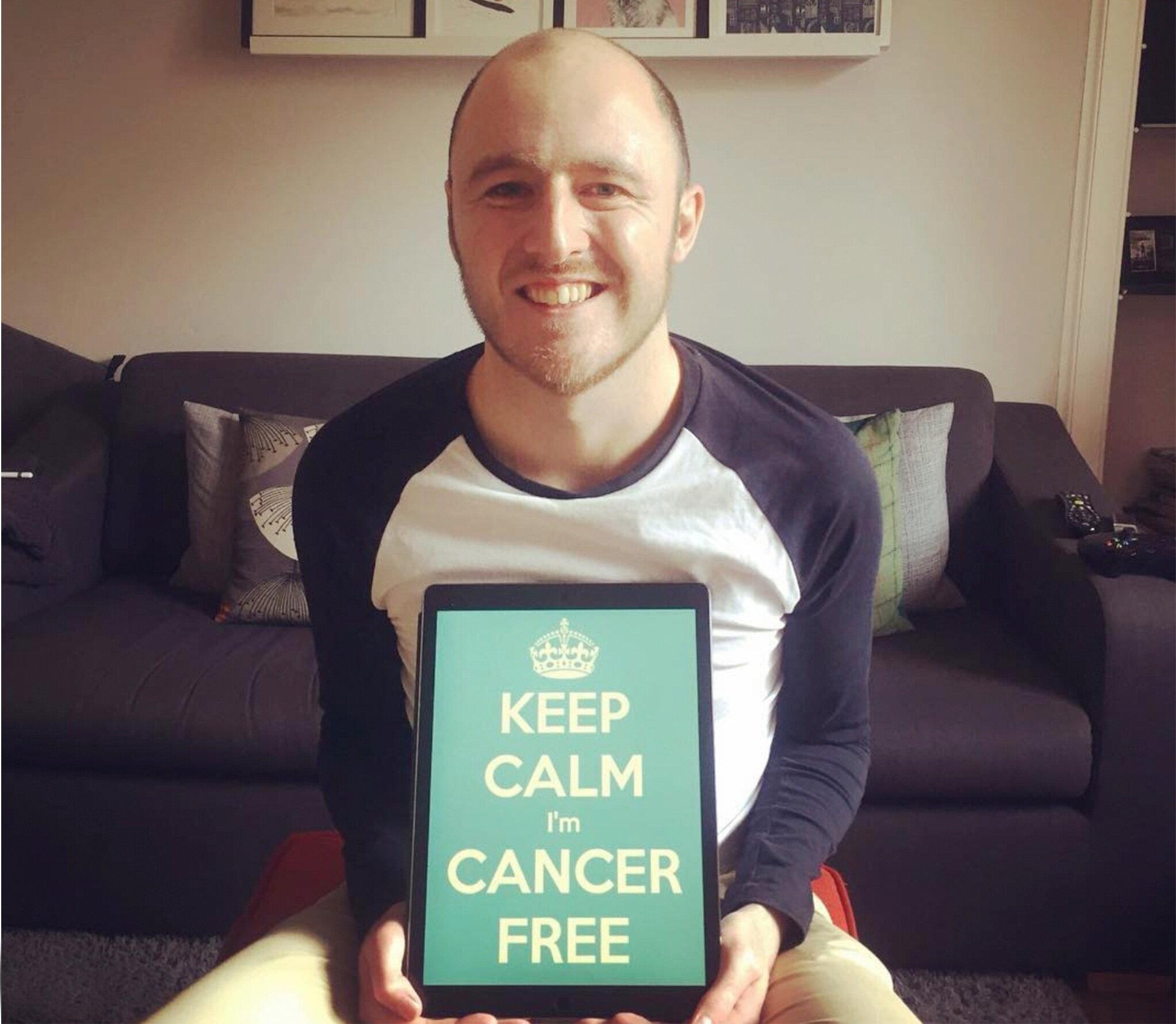

3 Years Cancer Free - Part 1

Woohoo! I’m three years cancer free today!

This is a deep dive into my journey from my original diagnosis, through to my all clear, and to life now. I’m a positive individual, so I plan to keep this positive where possible, although there might be some darker bits. I’m going to break this into CANCER, TRANSPLANT and FUTURE, so if you’re a bit squeamish, I’d recommend skipping the first bit!

CANCER

In November 2017, I was living a very normal life. I’d recently returned from a great holiday with my incredible wife and her family in Cyprus. That month, I had climbed the Munro Ben Wyvis with my best mates, climbing to the top in a magnificent mixture of sunshine and freezing snowstorms (classic Scotland). Oldmangrey was thriving, and I was taking on larger projects, attending markets and creating private commissions. In other words, I was having a great time!

But as November wore on, unbeknown to me, my body started to rapidly decline. The scary thing about Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) is just how subtle it can be, and for a lot of people, diagnosis of this blood cancer comes too late.

Although subtle, my symptoms were consistent with those seen in most AML patients. I wanted to take a moment to say what they were, in the hope that if you are ever unfortunate enough to spot them on you or a loved one, you can get bloods tested as soon as possible.

At the time, I remember three significant changes, but I’m sure there were others that don’t come to mind. Firstly, I noticed that I had some red freckle-like marks on my forearms. I now know that this is a petechial rash. As a freckly person, these didn’t overly concern me, as I’m used to freckles appearing and disappearing, but I soon came to understand what they were. A Petechial rash is a collection of pinpoint, round spots that appear on the skin as a result of bleeding. The bleeding causes the petechiae to appear red, brown or purple. Petechiae (puh-TEE-kee-ee) commonly appear in clusters and may look like a rash. Usually flat to the touch, petechiae don't lose colour when you press on them.

Petechial Rash Example

Secondly, I noticed that I was bruising easily. I played an intense game of football on the Tuesday of the week of my diagnosis, and upon saving the ball with my forearm, it immediately came up like a friction burn, with hundreds of blood spots around the area where the ball had hit me. I joked at the time about how hard the ball must’ve been hit and laughed it off. Although I classed this as a separate symptom, it is in fact related to the petechial rash. What links them is your platelets, your blood’s clotting mechanism. Without platelets, your blood can’t clot, so small insignificant scuffs were creating the rash, and the larger impacts were creating what I was referring to as bruises.

The final thing I remember, and probably the thing that worried me the most, was the feeling of fatigue. I’m not just referring to the feeling of tiredness that I’m sure you’re all familiar with, this was a much harder thing to shift. I was sleeping at the weekend for up to 12 hours and still waking up exhausted. I ran a relay marathon a few years before, and I can say that the feeling in the final part of a run is the closest thing I could compare to, except there’s no obvious reason for it and it doesn’t shift all day long. This is the only thing that post-cancer can still rear its ugly head from time to time. On those days, it’s ok to do absolutely nothing – as Tom Haverford once said – Treat Yo Self!

DAY OF DIAGNOSIS

On Friday November 24th 2017, I woke up with excruciating pain in my ankle. As I mentioned, I had played football on the Tuesday of that week and I had taken a slight knock to the area, but nothing that concerned me. However when I woke on the Friday I was so disorientated by the pain that I stumbled to the bathroom and very nearly fell through our glass shower unit. It felt like I’d broken straight through my ankle bone. I took pain killers, called my office to say that I wouldn’t be in, and made my way to A&E at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. I had already booked to see my GP later that day to enquire about the rash, bruising and fatigue, so I thought I’d also ask the doctors at the Royal about these symptoms as he they looked at my ankle, which was also heavily bruised.

I’d like to take a moment to say that throughout my treatment, the NHS in both Edinburgh and Glasgow have been nothing short of incredible. However, this particular visit wouldn’t have put them in a great light. I am yet to experience this kind of treatment since, and I presume that I never will again. The NHS is incredible.

Unfortunately for me, I was advised to head home from the Royal with Ibuprofen and told to rest my ankle. I had explained about my other symptoms, but the doctor I saw simply said that he wasn’t sure, and refused to take my bloods. I presume they were very busy, and unfortunately for me I’d told them that I was due to see my GP later that the day. Had the A+E doctor simply taken a vile of my blood he would’ve seen how dangerously low my platelet count was. He also sent me home with Ibuprofen; a blood thinner, and in other words the worst thing you can give someone who’s blood is already dangerously thin. Like I said, this is the only blip across the hundreds of health care professionals that I have dealt with in the three plus years of treatment so far. But in the future, I hope that that doctor doesn’t make the same mistake again. Had I felt too ill to make it to the GP later that day and cancelled the appointment, I potentially might not be here today.

Later on the Friday, I managed to get down to my GP’s practice. Myself and my wife were nervous in the waiting room because we knew something wasn’t right - that gut feeling you get when stuff is about to go South. I spent a long time in with the doctor and a student doctor. Looking back on this, I’m delighted that a student was there too; having spoken with doctors since, it’s rare that a GP without specialist knowledge would recognise and diagnose Leukaemia and so raising awareness of the disease and its symptoms within the profession is so important.

It might surprise you to know that Blood Cancer is the fifth most common Cancer in the UK, with over 40,000 yearly diagnoses. It’s also the third biggest killer, claiming more lives every year than breast or prostate cancer.

My bloods were taken late that afternoon, and due to an incredibly worried and generally incredible GP, he drove them straight to the lab. At 9.30pm that night I was sitting on the sofa after a Chinese takeaway with my foot raised for the pain in my ankle, when I received a phone call. It was the from the Oncology Ward at the Western General Hospital in Edinburgh. As an avid ‘House M.D.’ watcher, I knew all too well what Oncology meant, so I was prepared for the worst as myself and Nic, my wife, drove to the hospital. Later that night sat in a small room with Nic I was told that I had a blood cancer, but that I’d need a bone marrow biopsy to confirm what kind and how treatable it was. I was then informed of my platelet count…it was 12. To me, this was an arbitrary number, but the doctor confirmed that the usual range is 150-450 in an adult human. In short, I was dangerously low on clotting cells in my blood. I was also dangerously high in my white cell count. To keep it easy to understand, your white cells are your bloods soldiers and the normal range is 4.5 - 11 in your blood at any given time. I had 75. You see, Leukaemia lives in your white cells, so that big chunk of extra white cells was actually my cancer. It sits in your blood as useless cells that float about doing nothing but taking up the space that your white cells would normally. Unfortunately, your body doesn’t realise they’re there, so the disease gets worse and worse, eventually leaving you with a useless immune system. So, that night I received my first ever transfusion of platelets, and was surprised to learn that they’re yellow! The bloods I had taken that day were the first bloods I had on record, showing how lucky I’d been in my health up until that point.

The last thing I’d like to say on this, is how immensely proud I am of how I reacted to the news. In life you rarely get a chance to see the kind of person you will be when shit hits the fan. I got that chance, and I’m delighted to say that I acted my best. I was calm and I listened to all of the information. I took any piece of advice from my physicians to the letter and made sure that if they asked me to do something, I did it. I also focused on being pleasant to everyone I met; it’s important to be nice to be people who will inevitably be helping you win the biggest fight of your life. In short, don’t be a pleb! People who know me, know about my positive mindset, and I think that without it, I wouldn’t be here today. It’s something that you either have or you don’t, but I’m delighted to have had it all through this journey. Your mental health is seriously important, no more so than when you’re battling cancer.

WHY A TRANSPLANT?

When I was admitted to the Western General Hospital that weekend, an on-call doctor had quite flippantly mentioned that I would likely be unable to work for a year and asked if I had any siblings. I later discovered that these points were related to a harder fight I’d be taking on later the following year. After my first chemotherapy was complete, I was allowed to go home. It was nearly Christmas, I’d spent nearly a month stuck in my room in a hospital ward, and the team were keen to get me home for a break before my next chemotherapy round in January 2018. The morning before I was discharged, I was told by my incredible consultant, Dr Peter Johnson, that they had done further analysis on my bone marrow biopsy and my body’s response to the chemotherapy, and due to a genetic mutation in my white blood cells called FLT3, chemotherapy alone wouldn’t be enough to stop my Leukaemia from returning. FLT3 is a mutation present in 20-30% of AML patients and it is a protein that allows your white blood cells to constantly replicate. Normally, that wouldn’t be a problem, but because the white cells are where Leukaemia lives within your blood, and your body can’t tell the cells with the hidden Leukaemia apart from your regular white cells, it carries on growing the nasty wee buggers.

Dr Johnson revealed that to better guarantee that my Leukaemia would not return, I would need a stem cell transplant, and a Transplant Co-ordinator Liz Brown was brought in. They spoke to me and Nic for a while, before handing me a lot of paperwork and encouraging me to think it over before my next chemo. For me, it was a no brainer. I needed to get rid of my cancer, and they were telling me that this was the only option to prevent it from coming back. But it was a huge knock, as it meant a longer road of treatment and recovery, and even more risks. And there’s the huge issue of finding a matching donor. I underwent a second in-patient chemotherapy session in the January. Before this, I had to have a PICC line fitted; a thin, soft, long catheter (tube) that is inserted into a vein in your arm, giving your medication a more direct access to your blood. The best thing about it as a cancer patient, is that up until that point I had to have a Cannula fitted and changed every 3 days. That’s a lot of pin holes and arm hair to lose! The PICC was fitted with ease, and it made my life a lot easier. My bloods could be taken and my chemo and other medication given through it - amazing!

However, around one week into this January chemo, my arm around the PICC started to look red and swollen and grew increasingly painful. They marked the area in pen each day to track if the inflammation was spreading - it was. Unfortunately for me, it transpired I had a blood clot in my vein just north of the PICC line. This day was one of the lowest for me in my entire treatment, as I was at the low point of my chemotherapy and I had to have the PICC removed which meant three-day cannulas again. I also had to begin a pretty gruelling period of having to self administer blood thinner injections into my stomach. For sure, this was one of the worst parts of my treatment.

I’d like to take a moment to describe what my experience of chemotherapy was like. In the beginning, it was totally fine. You kid yourself that you might just feel fine. Essentially, I had your chemo (mine was bright purple!) and I fetl no different for probably 3-4 days. Those days are great! I read lots of books, watched tv, and enjoyed most of the NHS food. I’d say day five for me was when I started to feel poorly. When you first have chemo, there is a period where your body still has a lot of fight in it, the drugs haven’t had many days to compound their effect, and it takes time for the drugs to break down your immune system. However, when day five hit, I would then have a sharp decline for the next week and a bit. This is when joyous things like diarrhoea, fatigue, nose bleeds, temperatures, rigors (convulsions from temperature changes), mouth sores, vomiting and a whole cacophony of ‘lovely’ things began to set in. It’s definitely a shit time. All you can do is listen to the doctors and nurses, and rest. You need to allow your body to sleep whenever you can. Those of you reading this who have been unlucky enough to spend a night in hospital will know that they aren’t exactly quiet and calm environments. So getting rest when you desperately need it can be a challenge. I managed to find some solutions though; eye masks and ear buds. I wore an eye mask so often, that when my hair started to grow back in, I had a line around my head where the hair grew a lot slower under the band of my mask! An interesting look indeed. As well as rest, you need to look after your body as much as possible. I had to wash out my mouth routinely throughout each day with a special bacteria fighting solution, and I committed to a small workout every day. I’m glad that from the outset, I was resolute to listen and put into practice anything that the doctors and nurses told me to do.

Anyway…I’m conscious that this blog is now ‘UGE’, and that I’m probably only now talking to people like my mum. If you’re still here, and you’ve found this interesting, I’ll be releasing part two of this blog series on Wednesday this week, documenting the transplant itself. It’ll have lots of information in it about my journey and explain how anybody reading this could in fact save someone’s life. You could be a real life superhero!

Thanks for reading folks - speak Wednesday :)

Graeme